Parchment

Scribes completed their work on parchment, which most often came from the hides of sheep. If you recall from the layout of St. Gall, there was a place for sheep, goats, and cattle to be kept. Although they were probably used for food (meat and dairy) and clothing (wool, leather), the skins of these animals were also used to create vellum or parchment. To understand everything that the scribes had to go through and to better understand their needs in terms of space and storage for your scriptorium, we’re going to talk a bit about how to make parchment.

Ireland is known for its many, many sheep, and Rathlin Island is no different. Here is a picture of Rathlin Island sheep:

Rathlin Island Sheep

Photo credit: Paul Bowman / Foter / CC BY

Creating parchment was laborious process by today’s standards, and it all started with selecting the skin. Not all sheepskins were able to be used, and they had to be careful to pick those that were able to handle the processing. Sheep could have skin diseases or have been bitten by bugs or other animals, which could cause blemishes that weren’t able to be scraped away.

Don’t worry! They didn’t just toss out bad skins. Here’s a great blog post on what some scribes would do when faced with a piece of parchment that had a hole, deficiency, or blemish on it. (Sometimes what you had on hand wasn’t the best, but you made do with what you had, right?)

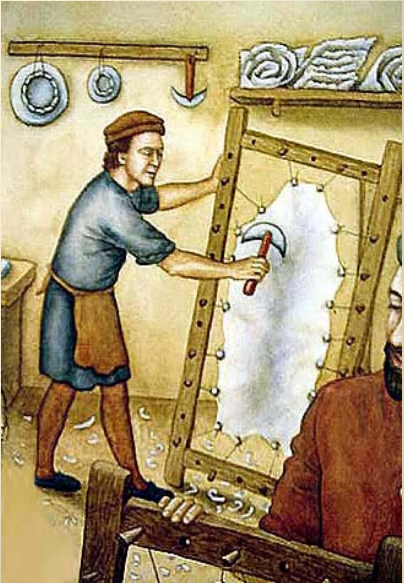

The skin was then left to soak in a bath of lime water, which loosened the hair and allowed it to be scraped away. It was then polished with a pumice stone to make it smoother and more even. The flesh side (the inside part of the skin), however, was not removed as easily. The skin would have to be stretched and attached in a frame of some sort to allow the flesh side to be scraped with a knife to remove the fat and loose bits of skin to make the entire parchment piece a uniform thickness. Then the skin was dried in the frame to keep it from shrinking back up before being cut out and prepared to be written upon.

Parchment being stretched and scraped (via)

Watch the video below to see the preparation process detailed above. This website also has the step-by-step process with pictures from Randy Asplund, a man who has created parchment from scratch several times. It’s fascinating to see the methods tested by modern people to see how labor-intensive the process was!

If you remember the video we watched on the context page, you’ll recall the rest of what happens. The dried skin was then cut into sheets, which had two sides: flesh side and hair side. Although the sides have been smoothed, they still have differences that let you know which side is which (such as the circles where the hair follicles were on the hair side). The sheets were folded in half to make a double folio (two-page) sheet. These sheets were then arranged into quires (or gatherings), which were readied to be bound in groups to the spine of the manuscript’s cover.

I want to know more

- “Parchment and Paper” from the New York Public Library via YouTube

- “Parchment” from Book and Byte (be sure to look through all of the sub-links on the right sidebar for detailed information about what happens to different types of parchment)

- “Forming quires” from The University of Nottingham

- “Parchment” from the Medieval Manuscript Manual

- “From Animal to Art: The Story of Parchment” from the Metropolitan Museum’s Pen and Parchment: Drawing in the Medieval Ages exhibit blog

- “The History and Technology of Parchment Making” from SCA Ltd (Australia)

- “Leather, Parchment, and Vellum” from the Papyri Pages