Text

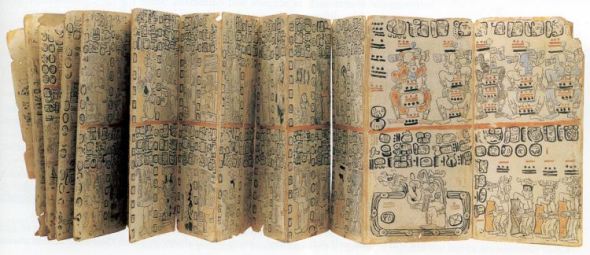

Each section of the manuscript is outlined with a red border (as seen on the previous Inks page). Scribes “did not think in terms of ‘pages,’ as we do, but wrote straight across these horizontal divisions, to the end of the section or chapter and then back to the next lower horizontal band; at times, even a glyph, or figure, is half on one ‘page”, half on the next” (Diringer, 2011, p. 431). The way the lines run, how the text breaks, and the way the pictures are set on the pages let researchers know how to read the pages. As you can see in the example from the Madrid Codex below, the folds do not correspond to “pages,” which are instead delineated by the red borders:

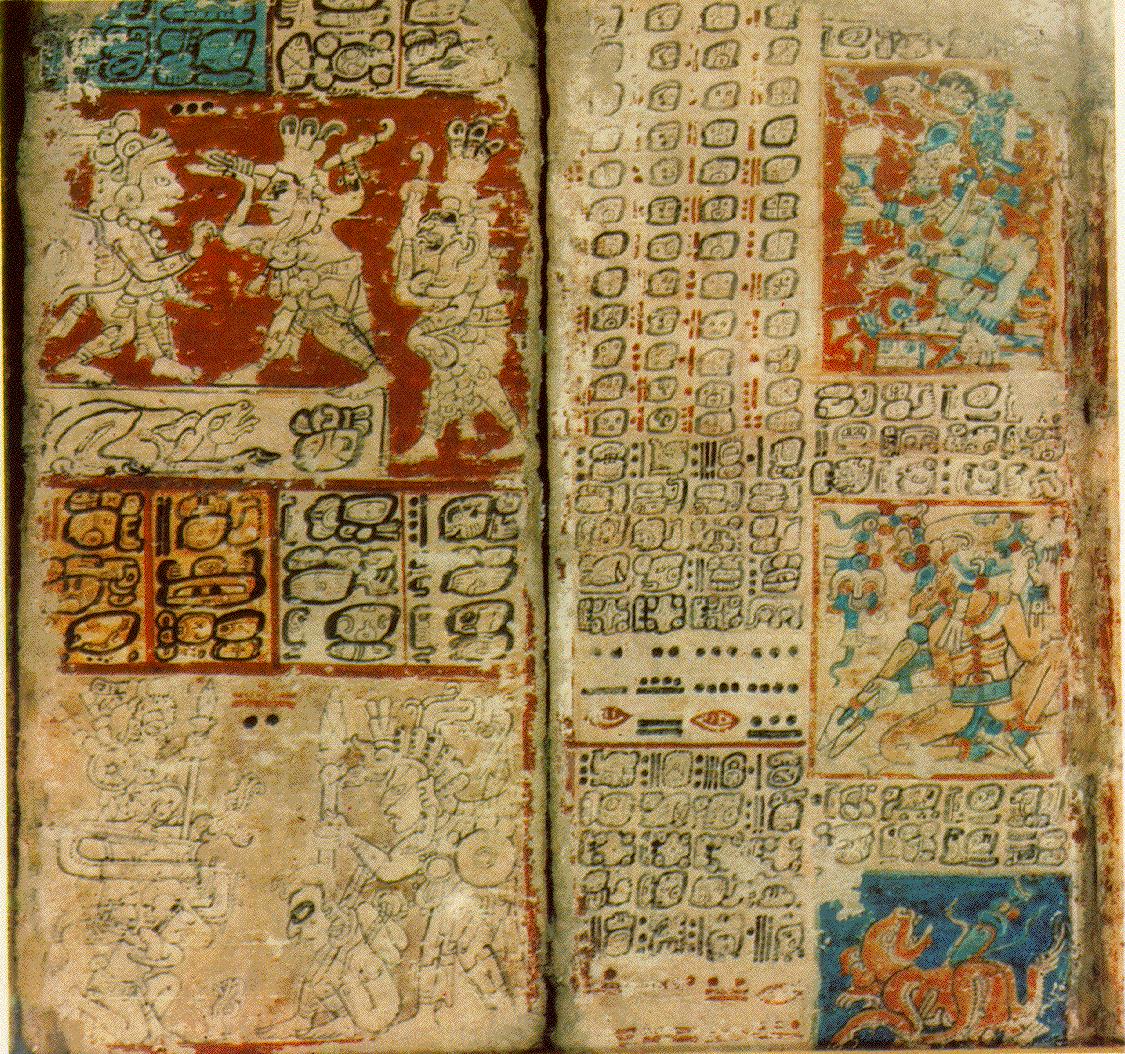

“The codex was painted in many colors (black, red, turquoise, tawny, blue, pink) with the outline of the hieroglyphs and images painted in black.” The text is read from left to right in each section and then top-to-bottom.

Sample page from the Dresden Codex (public domain)

Images of Mayan scribes at work often show them sitting on the floor with a codex in front of them on the ground. Researchers believe that the surviving codices may be re-creations of earlier texts, and it appears that the red lines for each section also acted as grid lines or rulings for the scribes to follow as to where each section’s information should go. (This is similar to a modern graphic artist determining the columns of his/her work before going ahead and adding the images and text to the created layout.) A scribe may have more than one folded section open at one time as he worked, depending on how far and to how many pages the section stretched across the codex.

Images were often of Maya deities and important figures, captioned with their names. Images often were placed on the right side of a folded page/section, as seen here:

Dresden Codex with images on right of each page/section (public domain)

Other times, a figure might stretch across sections and folds to correspond to the writing or information being told instead:

Close up of image stretching across pages