Dance, Dance, Dance is the rare book that makes you completely, thoroughly happy. Not stupid happy, ignoring the sadness and pain life can throw your way, but happily aware: fully cognizant of all the flaws in this world, but still finding it improbably beautiful.

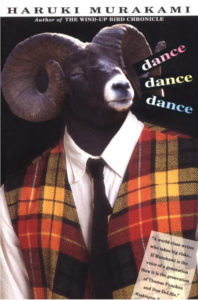

Why does Dance Dance Dance make me so joyful? Well, first, there’s that book cover, which is the edition my local library had, If that doesn’t make you smile a bit, well, umm, what’s wrong with you? It’s a sheep wearing a collared shirt, tie, and plaid sweater vest, for crying out loud.

But in all honesty the thing that makes the book so happy-making is what happens for its unnamed narrator. This is the fourth book he’s been in by Murakami, and in all of them he’s been emotionally withdrawn (something you can immediately feel and appreciate in his character, even if this book is your first encounter with him). In the first book the narrator appears in, Hear the Wind Sing, another character notes that he’s “Very zen.”

It serves him well, in a way, to float along and not be completely overwhelmed by the waves that come his way: he certainly is put through a lot. But it also keeps him emotionally distant, incapable of reaching his potential or really even feeling love. In the third book to feature the narrator, A Wild Sheep Chase, his wife leaves him at the start, most likely because of his emotional unavailability. But here, finally, in Dance Dance Dance, he is able to awaken: winter has fallen away, spring has sprung. You can see it stirring in the narrator as he reaches out and makes new friendships and even goes through the starts and stops of a new relationship with a hotel clerk.

If I could make a comparison, it’s like seeing a sad friend or relative suddenly grow, changing and reaching out, becoming that thing you always knew they could be. Even now it brings an almost inexplicable smile to my face, and that’s something to note in and of itself. Good literature, good art, should help us understand our fellow humans and appreciate their growths and triumphs.

This is made all the more palpable due to the darkness to be found in Dance Dance Dance. Just like its preceding three books, sadness lurks, as does death, Maybe even more than in the previous novels, and they were hardly carefree affairs.

Despite this, however, the book’s title is always at its center. Early on in the book, the narrator finds and has a discussion with the Sheep Man. Yes, there is a character called the Sheep Man (and despite the book cover above, he probably is only a guy in a sheep suit). But in that improbably Murakami way, he is very much real and very much not ridiculous. His otherworldliness is suggested in how all of his sentences consist of no spaces between the words: strange, but understandable.

In this early conversation, the narrator and the Sheep Man are tired. Withdrawn. The Sheep Man himself is feeling old. But he tells the narrator he can make his way back to life. “Yougottadance,” he says (86).

The narrator takes the advice to heart, and so does the book. Weird stuff keeps happening to the narrator, he keeps making friends (or renewing friendships), but then depression and loss also come along, threatening to derail it all. But he’s justgottakeepdancing, His finding a way to do this and encourage others to do so is part of the book’s magic.

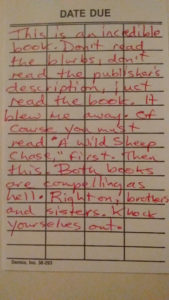

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world.

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world.

“This is an incredible book. Don’t read the blurbs, don’t read the publisher’s description, just read the book. It blew me away. Of course you must read “A Wild Sheep Chase,” first. Then this. Both books are compelling as hell. Right on, brothers and sisters. Knock yourselves out.”

As my fellow reader notes, it’s probably worth checking out A Wild Sheep Chase first, if not Wind/Pinball as well. You can appreciate this one without reading them, but it hits all the harder if you have the experience of all the narrator’s previous trials and tribulations.

Wherever you might be, however good or bad life might be going for you now in the moment, you need this book. You need it like a friend you just discovered and really should have known for your entire life.

Right on, my internet brothers and sisters, right on. Whether you do a little shuffle like this big, awkward Swede or something more graceful, we just gotta dance.

Wejustgottadance.

In non-BFS fashion, I’m going out on a limb and making a big statement I haven’t mulled over ad nauseum. In my cautious, middle child way, I like to settle into what I’m thinking and saying, but I felt compelled to make this leap after reading

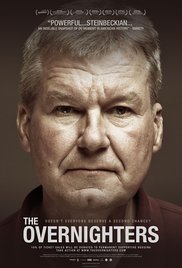

In non-BFS fashion, I’m going out on a limb and making a big statement I haven’t mulled over ad nauseum. In my cautious, middle child way, I like to settle into what I’m thinking and saying, but I felt compelled to make this leap after reading  I saw the documentary

I saw the documentary