Like a great river, Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels are deceptively slow-moving. Beneath their well-mannered, placid exteriors lie a current one inevitably succumbs to: when his characters finally come to regard the parts of their lives they have buried deep within, the emotional tidal wave caused is like little else in literature.

Like a great river, Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels are deceptively slow-moving. Beneath their well-mannered, placid exteriors lie a current one inevitably succumbs to: when his characters finally come to regard the parts of their lives they have buried deep within, the emotional tidal wave caused is like little else in literature.

The Remains of the Day

The early standout that garnered him major attention (an award-winning film adaptation certainly helped), 1989’s The Remains of the Day epitomizes Ishiguro’s modus operandi for almost all of his writing. The main character and first person narrator of the novel is Stevens, a butler of a great English manor house in the early and mid-twentieth century. He is a butler’s butler, a servant so committed to his task that he willingly contemplates changing his serious demeanor to attempt “some banter” with the new American owner of the manor where he works. Mr. Farraday seems to like little joking comments, so perhaps it is also expected of Stevens to respond in kind (though the reader can easily see Stevens is out of his depth here: so afraid is Stevens of offending his employer that his first attempt at humor doesn’t even register as a witticism). More, when Mr. Farraday suggests making a go of running the house with only four staff, Stevens accedes, even though doing so puts a strain on his health—we come to gather that Stevens is advanced in years, and is most probably in his 60s.

With how deferential and professional Stevens seems, it can take some time to realize that for all his attention to external detail, this butler is glossing over some life-altering facts about himself. Our first indication of this is a repeated reference and focus on a former housekeeper at the manor, Miss Kenton. Even though she has not worked there for twenty years in the novel’s present—1956—she seems a fixture in his thoughts and they do keep in touch: something he has not done with other former colleagues he recalls fondly yet cordially.

With how deferential and professional Stevens seems, it can take some time to realize that for all his attention to external detail, this butler is glossing over some life-altering facts about himself. Our first indication of this is a repeated reference and focus on a former housekeeper at the manor, Miss Kenton. Even though she has not worked there for twenty years in the novel’s present—1956—she seems a fixture in his thoughts and they do keep in touch: something he has not done with other former colleagues he recalls fondly yet cordially.

These indications come in ever-increasing waves, laying bare more and more of Stevens’s past life and work at the house for its former occupant, Lord Darlington. The subtlety with which they are revealed makes them all the more heart-breaking. At the novel’s middle point, Stevens recalls an important international conference Lord Darlington brought together at the house in 1923, attempting to have some of the harsher measures of the Versailles treaty reduced (at the end of World War I, the Allies exacted such extreme reparations from Germany that some historians believe they helped cause World War II).

At the same time as this conference, however, Stevens’s father, who has come to work at the manor in his old age, has a stroke and dies. Being a butler’s butler and knowing the importance of the conference for Lord Darlington (and therefore the world), Stevens refuses to cease his duties, continuing to deal with recalcitrant guests. He meticulously details the events of the evening, all while refusing to note the emotional toll it takes on him. In the midst of all the description and dialogue, it is only when a friendly visitor asks repeatedly if he’s alright that we realize the anguish which must be showing on Stevens’s face—and it’s confirmed a couple of paragraphs later, when Lord Darlington takes him aside as well, asking if he has been crying. Stevens just won’t admit to his true, honest emotions, even in the past tense as he recounts the evening.

It’s only at the novel’s end that Stevens can fully and finally admit to the mistakes of his past—to the anger and despair he feels at the trust he placed in his former employer, and what that trust has done to the rest of his life. After a little over two hundred pages spent in this character’s head, the release hammers the reader as hard as it does Stevens.

While there is an element of depression to these final events, the effect is something of a catharsis. Stevens’s life has been more empty than it should have been—and past choices cannot be revoked or wholly repaired—but he no longer pretends the damage does not exist. As another character notes to Stevens in the novel’s final moments while they watch the sun set, everyone is waiting for the joys an evening holds: the evening awaiting Stevens may not quite have been the one he desired or thought he was working for, but it is, nonetheless, one where he can make his own conscious choices.

Never Let Me Go

Where The Remains of the Day is a nod to the well-established “proper butler” and upstairs/downstairs storytelling of English tradition, Never Let Me Go tangles with a different fictional genre: science fiction and dystopia, with a flavor of alternate history. Added to the mix is that somewhat strange—to a middle-class American’s eyes—English institution, the boarding school.

Where The Remains of the Day is a nod to the well-established “proper butler” and upstairs/downstairs storytelling of English tradition, Never Let Me Go tangles with a different fictional genre: science fiction and dystopia, with a flavor of alternate history. Added to the mix is that somewhat strange—to a middle-class American’s eyes—English institution, the boarding school.

It’s a familiar fictional setting well established in many books, movies, and TV shows, however, so it’s in the slight differences to this formula that a reader begins to track the trouble beneath this novel’s proper British exterior. There’s the sadly reminiscent tone of the novel’s narrator, Kathy, for one, looking back at her days at Hailsham boarding school. There’s occasional hints about the future that awaits the students beyond the school’s grounds, and something seems a little off, or different, about it—particularly when one of the teachers insists the students be told more about what awaits them, which leads to some tense moments with the school’s leadership. And why does the school’s governor seem terrified of the students when she comes in for her monthly visit?

Even as this mystery deepens, we’re confronted by the human problems every person faces at that age. Who am I? What will I be in the future? And what about that attractive other person over there—do I… love them? Do they… love me? In Ishiguro’s hands, adolescence is treated with respect and depth.

Seen through the lens of Kathy’s memory, these events gain a greater magnitude as well. Moments that changed the forward projection of Kathy’s life, and her relationship with other students—particularly Tommy, another boy at school she felt a particularly strong connection to (but sadly never seemed to be able to start a relationship with). As we begin to understand the future awaiting the students from Hailsham, those missed opportunities begin to cut us more deeply, building to an impossible to forget moment, as Kathy looks out over an empty field in Norfolk. To others passing by, that field would have little, if any significance. For the reader, who has walked along through Kathy’s memories of what she had—and did not have—in her all too short life, it’s one they will never forget.

The Buried Giant

Ishiguro was apparently worried going into this novel’s publication, as it had more overt fantasy connotations, being set in Britain shortly after the reign of King Arthur. Dragons apparently exist, along with other magical creatures, and Merlin recently walked the enchanted isle. One has to wonder if this worry caused him to avoid too much overt fantasy, as other than for an ever-present magic that causes people to lose most of their long term memories, the novel proceeds fairly realistically.

Ishiguro was apparently worried going into this novel’s publication, as it had more overt fantasy connotations, being set in Britain shortly after the reign of King Arthur. Dragons apparently exist, along with other magical creatures, and Merlin recently walked the enchanted isle. One has to wonder if this worry caused him to avoid too much overt fantasy, as other than for an ever-present magic that causes people to lose most of their long term memories, the novel proceeds fairly realistically.

This reluctance is occasionally disappointing. While the title of the book certainly refers to the memory loss many of the characters are struggling with (and its cause), it also refers to what may be an actual, buried giant on Salisbury plain. Beatrice, one of the main characters, reminds her husband Axl of the necessity of passing by the buried giant’s hill in complete silence, also hinting at other sinister forces on the plain, but we never actually see these creatures. While the third person narrator of the book seems trustworthy, this creates a confusion over what is real and what is superstition—and while this is certainly in keeping with the book’s themes, it does feel like Ishiguro didn’t quite want to own the setting he chose. Among other elements, the book does have a real dragon, and Merlin did accomplish real magic with it, so not completely owning or dealing the ramifications of a world where magic and magical creatures exists feels like a shortcoming in an otherwise excellent book.

Being a genre enthusiast myself, I may have noticed this more than some other readers. But on a second read through, it was more noticeable to me, particularly given that the actual magic and fantasy Ishiguro used in the book is potent—delving into the very human and real world issues of loss and memory (are you noticing the similarities his other books?). In the novel’s present, elderly Britons Axl and Beatrice have been husband and wife for as long as they can remember—which is long, but they’re not entirely sure how long. Like everyone else in the book, a magical mist has deprived them of much of their long term memory. People only seem to remember what they see daily (sometimes hourly), and once that is gone, only the most persistent can even snatch at the phantom of a true recollection.

Beatrice and Axl begin a journey to visit their son, who lives in a village a few days away. They’re not sure why he’s no longer living with them, but they are certain they want to see him again. Throughout the course of their journey, they encounter Saxons, who seem to live in peace now with their Briton neighbors—but it wasn’t always that way. People still remember that there was a King Arthur who fought and protected them from the Saxons, but that war seems to be done and over with now.

This general lack of a long term memory (other than for the fuzziest of past, important details) makes for intriguing parallels to the real world. When we live in the now and forget how we arrived where we are, we cling to beliefs and superstitions for unknown, potentially spurious or damaging reasons. But we can also forget enormous pain, and the anger that can come with it. In the course of their journey, Beatrice and Axl meet a mighty Saxon warrior, who they come to a sort of accord with—the Saxon likes them well enough, but inside he holds a sharp hatred for all Britons, due to their mistreatment of him when he was young. Liking an individual but hating the group they are a part of is illogical when looked at in one way, of course, but it’s entirely realistic and human in practice.

In probing these themes, Ishiguro is sharply examining a post Cold War, 21st Century, where democracies the world over seem to be having an identity crisis: turning in on themselves now that they don’t have a clear and present exterior threat to form their identity around (or finding a new enemy within their own borders to form up against). While I could wish I didn’t live in such a seething kettle of repressed racism and hatred, I live in this time nonetheless and a book dealing with such powerful issues is one that cannot be over-valued.

That’s the grander drama of The Buried Giant. Beneath all these larger ideas is a more personal, human factor—ever present in Axl and Beatrice’s relationship. Arguably, Ishiguro’s best use of his fantasy setting is not the breath of the dragon, which has caused the long term memory issues, but the concept of a magical island, accessible only by a mysterious ferryman. Such an idea appears time and again in Arthurian legend, and Ishiguro uses it here to lay bare the human pains and fears we all have about death and losing those we most love. As Axl and Beatrice’s journey ends in an encounter with a mysterious ferryman, I found myself as moved as I had ever been with The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go.

o knock against serious drama, but there is something about a story that can blend comedic and serious themes just right: combining the two in the right mix can cause both elements to sing in ways they could not otherwise. Charles Dickens at his best (when he’s writing something I would want to read again, e.g., Little Dorrit) exemplifies this, as does one of the more Dickensian modern novels I have read, Luis Alberto Urrea’s Into the Beautiful North.

o knock against serious drama, but there is something about a story that can blend comedic and serious themes just right: combining the two in the right mix can cause both elements to sing in ways they could not otherwise. Charles Dickens at his best (when he’s writing something I would want to read again, e.g., Little Dorrit) exemplifies this, as does one of the more Dickensian modern novels I have read, Luis Alberto Urrea’s Into the Beautiful North.

Rom-coms have a clear formula: the potential love interests meet early on in the story, the potential love interests face obstacles in getting together, the love interests then finally get together (potentially facing more obstacles before they are for real together together). Simple.

Rom-coms have a clear formula: the potential love interests meet early on in the story, the potential love interests face obstacles in getting together, the love interests then finally get together (potentially facing more obstacles before they are for real together together). Simple. The novel begins with simple delight.

The novel begins with simple delight. Sometimes a reader is simply not prepared for the world they encounter within a book’s pages. “This dude is hard to like,” is my strongest memory from my first reading of

Sometimes a reader is simply not prepared for the world they encounter within a book’s pages. “This dude is hard to like,” is my strongest memory from my first reading of  There’s always a barrier between a reader and what they read—the reader knows they can always put the book down. This is particularly the case with a subject the reader thinks they know about already, as they’re further insulated from being affected by it, with their biases and previously drawn conclusions. But the best authors find a way to reduce or almost eliminate this barrier, to implode those implicit stances the reader places between them and the seemingly familiar concepts they’re encountering.

There’s always a barrier between a reader and what they read—the reader knows they can always put the book down. This is particularly the case with a subject the reader thinks they know about already, as they’re further insulated from being affected by it, with their biases and previously drawn conclusions. But the best authors find a way to reduce or almost eliminate this barrier, to implode those implicit stances the reader places between them and the seemingly familiar concepts they’re encountering.

Like a great river, Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels are deceptively slow-moving. Beneath their well-mannered, placid exteriors lie a current one inevitably succumbs to: when his characters finally come to regard the parts of their lives they have buried deep within, the emotional tidal wave caused is like little else in literature.

Like a great river, Kazuo Ishiguro’s novels are deceptively slow-moving. Beneath their well-mannered, placid exteriors lie a current one inevitably succumbs to: when his characters finally come to regard the parts of their lives they have buried deep within, the emotional tidal wave caused is like little else in literature. With how deferential and professional Stevens seems, it can take some time to realize that for all his attention to external detail, this butler is glossing over some life-altering facts about himself. Our first indication of this is a repeated reference and focus on a former housekeeper at the manor, Miss Kenton. Even though she has not worked there for twenty years in the novel’s present—1956—she seems a fixture in his thoughts and they do keep in touch: something he has not done with other former colleagues he recalls fondly yet cordially.

With how deferential and professional Stevens seems, it can take some time to realize that for all his attention to external detail, this butler is glossing over some life-altering facts about himself. Our first indication of this is a repeated reference and focus on a former housekeeper at the manor, Miss Kenton. Even though she has not worked there for twenty years in the novel’s present—1956—she seems a fixture in his thoughts and they do keep in touch: something he has not done with other former colleagues he recalls fondly yet cordially. Where The Remains of the Day is a nod to the well-established “proper butler” and upstairs/downstairs storytelling of English tradition, Never Let Me Go tangles with a different fictional genre: science fiction and dystopia, with a flavor of alternate history. Added to the mix is that somewhat strange—to a middle-class American’s eyes—English institution, the boarding school.

Where The Remains of the Day is a nod to the well-established “proper butler” and upstairs/downstairs storytelling of English tradition, Never Let Me Go tangles with a different fictional genre: science fiction and dystopia, with a flavor of alternate history. Added to the mix is that somewhat strange—to a middle-class American’s eyes—English institution, the boarding school. Ishiguro was apparently worried going into this novel’s publication, as it had more overt fantasy connotations, being set in Britain shortly after the reign of King Arthur. Dragons apparently exist, along with other magical creatures, and Merlin recently walked the enchanted isle. One has to wonder if this worry caused him to avoid too much overt fantasy, as other than for an ever-present magic that causes people to lose most of their long term memories, the novel proceeds fairly realistically.

Ishiguro was apparently worried going into this novel’s publication, as it had more overt fantasy connotations, being set in Britain shortly after the reign of King Arthur. Dragons apparently exist, along with other magical creatures, and Merlin recently walked the enchanted isle. One has to wonder if this worry caused him to avoid too much overt fantasy, as other than for an ever-present magic that causes people to lose most of their long term memories, the novel proceeds fairly realistically. In a year already marred by

In a year already marred by  (AKA “An Appreciation of The Last Jedi by a Middle-aged Cis White Dude, Since Supposedly We All Hate This Movie”)

(AKA “An Appreciation of The Last Jedi by a Middle-aged Cis White Dude, Since Supposedly We All Hate This Movie”) On the more difficult to parse side are comments that can still be rejected fairly off hand. One that repeatedly comes up is that Rian Johnson, the director of The Last Jedi, is a hack: someone that just doesn’t know how to make a good movie. A brief look at Johnson’s body of work makes this infinitely mockable, just based on the strength of

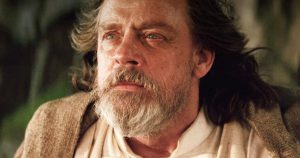

On the more difficult to parse side are comments that can still be rejected fairly off hand. One that repeatedly comes up is that Rian Johnson, the director of The Last Jedi, is a hack: someone that just doesn’t know how to make a good movie. A brief look at Johnson’s body of work makes this infinitely mockable, just based on the strength of  The Last Jedi throws this all on its head. Luke has given up, marooning himself on an island on a remote planet that almost no one knows how to find. This act even threw Mark Hamill for a loop: he’s quoted in the special features of the movie (and elsewhere) as not being on board with the changes to his character—but as a professional and a classy guy, he still endeavored to make Johnson’s vision work. To Hamill and many other fans, Luke Skywalker is one of the most hopeful characters in cinematic history, and Rian Johnson’s script seems to do away with all that, presenting a saddened, broken failure of a man at the movie’s opening.

The Last Jedi throws this all on its head. Luke has given up, marooning himself on an island on a remote planet that almost no one knows how to find. This act even threw Mark Hamill for a loop: he’s quoted in the special features of the movie (and elsewhere) as not being on board with the changes to his character—but as a professional and a classy guy, he still endeavored to make Johnson’s vision work. To Hamill and many other fans, Luke Skywalker is one of the most hopeful characters in cinematic history, and Rian Johnson’s script seems to do away with all that, presenting a saddened, broken failure of a man at the movie’s opening.

First is the irony of “Crying all the time.” Oh, Rey gets upset about her parents leaving her as a child on a desert planet, where she has to eke out a barren and miserable existence (where she can all too easily envision herself turning into one of the old, shriveled, and dejected women around her)? I hope you also complain about Luke’s abject dismay and horror at learning his father is Darth Vader, you worthless excuse for a person with the emotional capacity of a croquet mallet.

First is the irony of “Crying all the time.” Oh, Rey gets upset about her parents leaving her as a child on a desert planet, where she has to eke out a barren and miserable existence (where she can all too easily envision herself turning into one of the old, shriveled, and dejected women around her)? I hope you also complain about Luke’s abject dismay and horror at learning his father is Darth Vader, you worthless excuse for a person with the emotional capacity of a croquet mallet. And why are you so upset about women in the sequels, you misogynistic excuse for a wart? In the original trilogy, Leia outranked Han (and held her own against his attempts at verbal wit), while blasting up the Death Star, Cloud City, and Endor like the boys. Mon Mothma was the freaking leader of the Rebellion, not Han or Luke. This stuff ain’t new, and I question your ability to know, comprehend, or understand the movies you supposedly are a fan of. Not that I’m surprised, given your ability to hold less sentiment than a teaspoon.

And why are you so upset about women in the sequels, you misogynistic excuse for a wart? In the original trilogy, Leia outranked Han (and held her own against his attempts at verbal wit), while blasting up the Death Star, Cloud City, and Endor like the boys. Mon Mothma was the freaking leader of the Rebellion, not Han or Luke. This stuff ain’t new, and I question your ability to know, comprehend, or understand the movies you supposedly are a fan of. Not that I’m surprised, given your ability to hold less sentiment than a teaspoon. Kelly Marie Tran’s Rose has every right to despise arms dealers and those who profit from war. She’s lived her entire life in a war-torn galaxy: a galaxy torn apart because a bunch of emotionally stunted force users didn’t learn to grapple with their very real trauma. What do the prequels look like if the Jedi hadn’t just preached peace (and

Kelly Marie Tran’s Rose has every right to despise arms dealers and those who profit from war. She’s lived her entire life in a war-torn galaxy: a galaxy torn apart because a bunch of emotionally stunted force users didn’t learn to grapple with their very real trauma. What do the prequels look like if the Jedi hadn’t just preached peace (and