The greatest friendships in life are often the unexpected ones—the ones you didn’t know you could or should look for. The other kid on the playground you didn’t notice at first; the random post from a kindred spirit on the internet; each one the unique support you didn’t even know you need.

When you make a major move as Jessica and I did four years ago, you of course hope you’ll find new friendships in your new location. But there’s always the lurking fear that you won’t make any new connections—especially strong friendships. Having made major moves before in adulthood, we both knew how hard this could be. Most adults our age are already balancing their life around established friends and family, and oftentimes their kids. Adding a new friendship to that equation rarely happens: the “Yes, we should do something sometime” statements are all too often not followed up on.

So it was wonderful to hear that Jessica’s new job included a lunchtime group of the people who worked near her in the library: amusing lines and anecdotes were repeated for me when she came home at night, and she told me that much of the lunchtime chatter passed over jigsaw puzzles that were painstakingly sorted and assembled on the break room table. Jigsaw puzzles have driven me nutty since I was a child, but they took on a new light for me here—if they were part of what was making my wife happy in this new place we had found ourselves in, they couldn’t be all that bad.

One co-worker’s name came up repeatedly: Randy Rasmussen. He was older than us—old enough to be in our parents’ generation—though he came across as anything but a stuffy relative. A genial, kind, witty man whose leukemia had recently gone into remission, it seemed like he had watched every TV show and film ever made (he had even published four books about movies!). Need to know something about Orson Welles or a Hammer horror film? Randy was your man. Want to talk about an episode of Bewitched? Randy was most definitely your man: Elizabeth Montgomery was the most beautiful, elegant woman who ever lived, if you asked him.

While maybe not yet a friendship, this workplace acquaintanceship seemed the start of one—for Jessica and me. I had begun to know Randy better as well, since I frequently came in to eat lunch with Jessica and the rest of her lunchtime crew. And so the weeks and months passed, with us getting to know Randy better and better.

He talked about about his vast movie collection and how he organized it, noting that he was going through the bookcase devoted to his favorites—watching one movie a night—determining if they still deserved a place on those hallowed shelves. He recommended movies to me and Jessica, describing Before Sunrise as “the best movie of the 90s” (we watched it and rather had to agree). And he mentioned valuing his days more, since the leukemia went into remission—that he found them all the more precious now. One time, walking back from the dining center, he noted one of his favorite spots on the University of North Dakota campus, where the English Coulee ripple-roared over a small ledge of rocks. Though Jessica and I had paused over that bridge many times before, we did so again, savoring the sight and sound anew.

Why is it so many of the best experiences are shared? A thing you find and love alone seems a softly singing solo, while sharing that same thing with another seems to transform it into a glistening harmony.

I find myself sitting and remembering so many things like this about Randy. Having him over in the fall of 2019 to listen to an old radio drama, “Sorry, Wrong Number,” a gem I had never heard of before. Eating a Thanksgiving meal with him just a few weeks later. And going to watch Knives Out last January. The theater was empty except for our group and it felt like we were watching it on a big screen in our living room, joking and talking during the movie like we never would with a larger audience around us.

Hanging around those happy moments from a little over a year ago was the news that the doctors were not happy about Randy’s numbers, that the leukemia might be relapsing. It was knowledge we did our best to ignore around the times we shared, though it grew impossible to do so as the covid pandemic took hold and he asked us to drive him back from the leukemia treatments that seemed to make no difference—Randy was not improving. We offered to drive him in as well, wanting to do more for him, but he didn’t like to be a bother.

If that were one thing you could fault Randy for, it was that independence and desire not to be a bother. At the same time, how dare I push in on his desire for independence and privacy, things I very much value myself? But helping him with his appointments and keeping up with him periodically was all Jessica and I had to give to Randy, and it never seemed enough. It wasn’t enough, or he’d still be here.

Which makes me even more angry—in a world where there isn’t enough kindness, in a year that was all too short on kindness, why did 2020 have to add leukemia claiming the nicest man man in North Dakota to its list of horrors? Randy may never have accepted the title of “nicest man in North Dakota” for himself—he was too nice to claim it for himself—but a friend of ours bestowed it upon him and I have yet to hear a person dispute that moniker who even passingly knew Randy.

Now, even though Randy passed away over a month ago, the anger still returns. The distancing required of the current covid pandemic makes it seem he still has to be out there, like everyone else I’m not seeing in person at the moment. He’s just a phone call or email away, right? My mind prefers to think like that, despite knowing better. When I accept it, though, when I remind myself fully that he is gone and that we will never eat lunch together again, I find myself grateful that I even got to know him. In the small space of time granted by his leukemia’s remission, there was an opening for the glimmers of a new friendship, and I will never forget that.

And I will always remember you, Randy, when I start a movie… when I walk across the English Coulee… and when I think about the all too few days and minutes that life gives us.

In a year already marred by

In a year already marred by  (Important, pre-blog post note, as this was drafted three weeks ago: opinions are opinions and not to be confused with facts)

(Important, pre-blog post note, as this was drafted three weeks ago: opinions are opinions and not to be confused with facts) The problem with that? Opinions are like butts: everybody got one. Once we’re Covid free, singles aren’t going to stop liking their singlehood for the time being (or for some, wishing and longing they were not single). Relationship holders are not going to stop loving (or pretending to love) their relationship. And meddlesome relatives and friends aren’t going to stop suggesting to the single person they know that the right man/woman/person for them might be just around the corner.

The problem with that? Opinions are like butts: everybody got one. Once we’re Covid free, singles aren’t going to stop liking their singlehood for the time being (or for some, wishing and longing they were not single). Relationship holders are not going to stop loving (or pretending to love) their relationship. And meddlesome relatives and friends aren’t going to stop suggesting to the single person they know that the right man/woman/person for them might be just around the corner. If everybody got opinions, are we condemned then to stand in our wrongness and be wrong and get used to it (no matter how amusing it was

If everybody got opinions, are we condemned then to stand in our wrongness and be wrong and get used to it (no matter how amusing it was

Of course, there are incongruities to memory. Things excised, things brought forward–the mind and desire altering things in ways you don’t realize until reality presents the contrast to you with crystal clarity. During that return visit to south Minneapolis, the

Of course, there are incongruities to memory. Things excised, things brought forward–the mind and desire altering things in ways you don’t realize until reality presents the contrast to you with crystal clarity. During that return visit to south Minneapolis, the

It was a hard line to swallow back in my college years. ‘This isn’t true,’ I thought. I was reading The World According to Garp for a Contemporary Literature course and reacting to this line: “Rape, Garp thought, made men feel guilt by association” (p. 209).

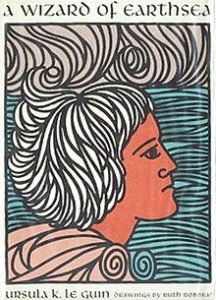

It was a hard line to swallow back in my college years. ‘This isn’t true,’ I thought. I was reading The World According to Garp for a Contemporary Literature course and reacting to this line: “Rape, Garp thought, made men feel guilt by association” (p. 209). Mastery. It’s the focus of a book I just finished, and very much relevant here. In Ursula K, Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, the main character is a man as powerful as many men want to be. Magic comes to him easily, and he learns far more quickly than his fellows. Yet the central thing this mighty protagonist must face is not some external power (a dragon, another wizard, etc.), but his own shadow, his own darkness. A thing of his own creation that threatens to subsume him.

Mastery. It’s the focus of a book I just finished, and very much relevant here. In Ursula K, Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, the main character is a man as powerful as many men want to be. Magic comes to him easily, and he learns far more quickly than his fellows. Yet the central thing this mighty protagonist must face is not some external power (a dragon, another wizard, etc.), but his own shadow, his own darkness. A thing of his own creation that threatens to subsume him. Columbine happened not long after I graduated from high school, and it disturbed me to the core. While it wasn’t the first such mass shooting, it was the one that slapped me awake. Nor did it seem outside the realm of possibility for it to have happened in the school I had just graduated from. After all, there weren’t (and aren’t) all that many dissimilarities between a suburb in Minneapolis and a suburb in Denver.

Columbine happened not long after I graduated from high school, and it disturbed me to the core. While it wasn’t the first such mass shooting, it was the one that slapped me awake. Nor did it seem outside the realm of possibility for it to have happened in the school I had just graduated from. After all, there weren’t (and aren’t) all that many dissimilarities between a suburb in Minneapolis and a suburb in Denver.