(AKA “An Appreciation of The Last Jedi by a Middle-aged Cis White Dude, Since Supposedly We All Hate This Movie”)

(AKA “An Appreciation of The Last Jedi by a Middle-aged Cis White Dude, Since Supposedly We All Hate This Movie”)

Even if you don’t give a fig for the new Star Wars movies, you’ve most certainly heard about them somewhere through the grapevine (fig… vine?): they’re either the greatest thing since sliced bread/the original movie trilogy, or they’re those movie things with fans so terrible they make the actors in them cancel their social media accounts… and sometimes their acting careers.

Nowhere is this divide clearer than for the second movie in the Star Wars sequel trilogy, The Last Jedi. Even as a fan of Star Wars and an observer of its fandom, it’s kind of hard to tell where the consensus lands for this one (if such a thing can be found among millions or billions of people) and if there are issues, what those truly are. Some of the complaints can be discounted offhand by emotionally stunted people that probably need some therapy, while others are truly revolting and/or mysoginistic, with supposed “fan” cuts that remove every female giving orders in the movie. We see you, people, and we know what you’re about.

On the more difficult to parse side are comments that can still be rejected fairly off hand. One that repeatedly comes up is that Rian Johnson, the director of The Last Jedi, is a hack: someone that just doesn’t know how to make a good movie. A brief look at Johnson’s body of work makes this infinitely mockable, just based on the strength of Brick and Looper alone (now with Knives Out added to the mix). Even if you don’t want to watch any of of his other movies, the visual power of The Last Jedi alone discounts this claim. You don’t forget things like Snoke’s red throne room if you watch this movie; it is too menacingly gorgeous. Calling Johnson a hack is one of those “internet takedowns” that only work if you’re talking to a group that will already agree with anything you have to say on a subject. You can give each other an electronic high-five or fist bump all you want, but don’t expect the rest of the world to agree with you so easily.

On the more difficult to parse side are comments that can still be rejected fairly off hand. One that repeatedly comes up is that Rian Johnson, the director of The Last Jedi, is a hack: someone that just doesn’t know how to make a good movie. A brief look at Johnson’s body of work makes this infinitely mockable, just based on the strength of Brick and Looper alone (now with Knives Out added to the mix). Even if you don’t want to watch any of of his other movies, the visual power of The Last Jedi alone discounts this claim. You don’t forget things like Snoke’s red throne room if you watch this movie; it is too menacingly gorgeous. Calling Johnson a hack is one of those “internet takedowns” that only work if you’re talking to a group that will already agree with anything you have to say on a subject. You can give each other an electronic high-five or fist bump all you want, but don’t expect the rest of the world to agree with you so easily.

The Actual Problem With The Last Jedi (if there really is one):

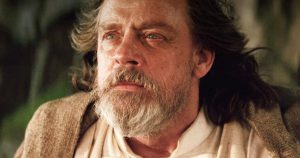

Cutting past the misogyny and internet vitriol, one can find a fairly consistent complaint about the movie, its characters and its themes: one which can basically be summed up as the “Luke Skywalker problem.” Fans of the original trilogy had decades to celebrate Luke’s journey, to look up to it and to celebrate it. Adding to the pedestal effect created by the emotional power of the original movies are the Star Wars fiction series that started up in the 1990s with the beloved trilogy by Timothy Zahn. Sure, Luke has some flaws and suffers setbacks in these books, but he’s always the hero—and he emerges in the right and victorious yet again.

The Last Jedi throws this all on its head. Luke has given up, marooning himself on an island on a remote planet that almost no one knows how to find. This act even threw Mark Hamill for a loop: he’s quoted in the special features of the movie (and elsewhere) as not being on board with the changes to his character—but as a professional and a classy guy, he still endeavored to make Johnson’s vision work. To Hamill and many other fans, Luke Skywalker is one of the most hopeful characters in cinematic history, and Rian Johnson’s script seems to do away with all that, presenting a saddened, broken failure of a man at the movie’s opening.

The Last Jedi throws this all on its head. Luke has given up, marooning himself on an island on a remote planet that almost no one knows how to find. This act even threw Mark Hamill for a loop: he’s quoted in the special features of the movie (and elsewhere) as not being on board with the changes to his character—but as a professional and a classy guy, he still endeavored to make Johnson’s vision work. To Hamill and many other fans, Luke Skywalker is one of the most hopeful characters in cinematic history, and Rian Johnson’s script seems to do away with all that, presenting a saddened, broken failure of a man at the movie’s opening.

To many, that is the movie’s entire portrayal, with maybe a slight hand wave toward Luke still being amazing at the end of the movie (but not enough to make up for what Rian Johnson and Disney have “done” to their hero). Luke simply isn’t allowed to be his hopeful and heroic self, they claim, nor is he allowed to be an awesome Jedi sage, like Yoda.

Just how awesome is Yoda, though? Yes, he’s able to do things Luke can only marvel at when he himself was learning in the original trilogy, but for all the power and knowledge of the force he demonstrates, both he and Obi-Wan Kenobi are broken old men in the middle three movies: they have flat out failed and are in hiding as well. And worse than Luke, they don’t seem to have changed much from the experience. Kenobi regrets that he did not teach his former pupil as well as Yoda would have done, but the truths they cling to have not shifted all that much.

The Last Jedi is an Affirmation of Luke and the Star Wars Universe, Not a Rejection:

Indeed, it is in Luke’s differences from his mentors that The Last Jedi actually holds true to the character. Hope is a wonderful thing, but you can hope in the wrong direction, and hopes may be broken: is there a depression more complete than failure and disillusionment? Everything Luke worked toward in the original trilogy, and the decades since, has gone for naught. The Empire has re-risen as the First Order, and he almost killed his sister’s (and best friend’s) son in a moment of weakness, allowing that boy to fall to the dark side.

Rather than re-treading the sage mystic routine that characterizes Obi-Wan and Yoda in the original trilogy, the character arc for Luke in The Last Jedi allows him to be a real, flesh-and-blood person. Beyond that, it also allows a viewer to value just who Luke is. We miss Luke’s hopefulness, but we can appreciate it all the more when we see that his hopefulness is what energizes Rey so much. Rey isn’t just the new hero of the sequel trilogy, she’s also the person that reminds Luke of who and what he truly is—and that has very little to do with his failure.

Even though it is the middle of a trilogy, The Last Jedi is also the eighth episode of a saga that is nine movies long. For a story to have power, for a story to resonate with its viewer, it has to find something in itself that will linger with its audience. And in a generational saga like this one, stretching across decades, it’s almost impossible not to consider the impact of legacy.

The Last Jedi asks some tough questions about this saga’s legacy—the legacy that its characters want, and the legacy that its viewers want. In watching it, some viewers seem to want a return to safety, to where things ended in its happy middle. It’s an understandable urge, but one that is not true to the saga that they love (or the world that they live in). Change is what characterizes Star Wars. It saw the end of a government that had lasted for centuries in the prequels, it sought an end to the autocratic regime that replaced that former government in the original trilogy, and now it asks what the future will hold in the sequel trilogy.

By asking the tough questions, Rian Johnson was able to identify the beating heart at the center of Luke, Rey, and the entire franchise: hope.

First is the irony of “Crying all the time.” Oh, Rey gets upset about her parents leaving her as a child on a desert planet, where she has to eke out a barren and miserable existence (where she can all too easily envision herself turning into one of the old, shriveled, and dejected women around her)? I hope you also complain about Luke’s abject dismay and horror at learning his father is Darth Vader, you worthless excuse for a person with the emotional capacity of a croquet mallet.

First is the irony of “Crying all the time.” Oh, Rey gets upset about her parents leaving her as a child on a desert planet, where she has to eke out a barren and miserable existence (where she can all too easily envision herself turning into one of the old, shriveled, and dejected women around her)? I hope you also complain about Luke’s abject dismay and horror at learning his father is Darth Vader, you worthless excuse for a person with the emotional capacity of a croquet mallet. And why are you so upset about women in the sequels, you misogynistic excuse for a wart? In the original trilogy, Leia outranked Han (and held her own against his attempts at verbal wit), while blasting up the Death Star, Cloud City, and Endor like the boys. Mon Mothma was the freaking leader of the Rebellion, not Han or Luke. This stuff ain’t new, and I question your ability to know, comprehend, or understand the movies you supposedly are a fan of. Not that I’m surprised, given your ability to hold less sentiment than a teaspoon.

And why are you so upset about women in the sequels, you misogynistic excuse for a wart? In the original trilogy, Leia outranked Han (and held her own against his attempts at verbal wit), while blasting up the Death Star, Cloud City, and Endor like the boys. Mon Mothma was the freaking leader of the Rebellion, not Han or Luke. This stuff ain’t new, and I question your ability to know, comprehend, or understand the movies you supposedly are a fan of. Not that I’m surprised, given your ability to hold less sentiment than a teaspoon. Kelly Marie Tran’s Rose has every right to despise arms dealers and those who profit from war. She’s lived her entire life in a war-torn galaxy: a galaxy torn apart because a bunch of emotionally stunted force users didn’t learn to grapple with their very real trauma. What do the prequels look like if the Jedi hadn’t just preached peace (and

Kelly Marie Tran’s Rose has every right to despise arms dealers and those who profit from war. She’s lived her entire life in a war-torn galaxy: a galaxy torn apart because a bunch of emotionally stunted force users didn’t learn to grapple with their very real trauma. What do the prequels look like if the Jedi hadn’t just preached peace (and  Friday night, Jessica and I had a decision to make: were we going to see Lego Batman or Moonlight? We ended up choosing the latter, partially under the logic that plenty of people were going to see Lego Batman, and we might as well reward the theater for picking the less popular but more serious movie, which had just won an Oscar for Best Picture.

Friday night, Jessica and I had a decision to make: were we going to see Lego Batman or Moonlight? We ended up choosing the latter, partially under the logic that plenty of people were going to see Lego Batman, and we might as well reward the theater for picking the less popular but more serious movie, which had just won an Oscar for Best Picture. detective—surprisingly so, considering the Robert Downey, jr/Jude Law movie of 2009 should have made me feel tapped out on the character and concept… at least for awhile (tell

detective—surprisingly so, considering the Robert Downey, jr/Jude Law movie of 2009 should have made me feel tapped out on the character and concept… at least for awhile (tell  They’re everywhere. They’re in commercials and they’re all over the internet. They keep the movie you’re about to watch from starting for 15-20 minutes (unless you’re smart and show up 15-20 minutes late, like a certain Viking and Celt enjoy doing). And sometimes, previews do what they’re supposed to do, getting you excited about an upcoming movie. Frequently, though, you can wonder who put the darn thing together.

They’re everywhere. They’re in commercials and they’re all over the internet. They keep the movie you’re about to watch from starting for 15-20 minutes (unless you’re smart and show up 15-20 minutes late, like a certain Viking and Celt enjoy doing). And sometimes, previews do what they’re supposed to do, getting you excited about an upcoming movie. Frequently, though, you can wonder who put the darn thing together. Okay, so… I got a little excited two weeks ago when the Celt found a preview for

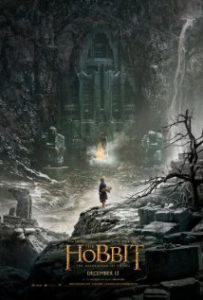

Okay, so… I got a little excited two weeks ago when the Celt found a preview for  JRR Tolkien is one of my favorite authors. The Lord of the Rings is full of the stuff of life: themes and values worth thinking about, running right along great characters and a fantastic story. The Hobbit is also great fun in a more lighthearted way, with a delightful focus on how Bilbo grows and changes over his journey.

JRR Tolkien is one of my favorite authors. The Lord of the Rings is full of the stuff of life: themes and values worth thinking about, running right along great characters and a fantastic story. The Hobbit is also great fun in a more lighthearted way, with a delightful focus on how Bilbo grows and changes over his journey.