In a year already marred by insurrectionists storming the U.S. capitol building to dispute the results of an election in which hardly any instances of voter fraud occurred, I find myself comforted by Haruki Murakami’s best novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle—and disturbed by its all too accurate portrayal of the dark side of humanity.

In a year already marred by insurrectionists storming the U.S. capitol building to dispute the results of an election in which hardly any instances of voter fraud occurred, I find myself comforted by Haruki Murakami’s best novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle—and disturbed by its all too accurate portrayal of the dark side of humanity.

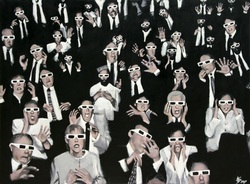

Why is it that evil so easily seems to grow? How do the seeds of dissension so easily spread? Murakami’s novel rightly identifies media as one cause, with those who earn its seemingly random favor gaining a strange power to manipulate those around them. At one point the book’s main character, Toru Okada, is warned to be careful: “Those people are always glued to the television set. That is why you are so disliked here. They are very fond of your wife’s elder brother” (pg. 572).

Nor is it just being in media that confers power—it’s also how the media is used. Toru’s brother-in-law is so dangerous because he does not seem to hold any consistent values (other than the increasing of his own power). Rather than being problematic to his supporters and viewers, this lack of consistency actually works in the brother-in-law’s favor, which Murakami notes in a passage that will echo alarmingly to anyone who has paid any amount of attention to modern media (and politics), let alone the past week: “Consistency and an established worldview were excess baggage in the intellectual mobile warfare that flared up in the mass media’s tiny time segments, and it was his great advantage to be free of such things (pg. 75-76).”

It’s not all down to the media of course—hatred and evil find other ways to spread… sometimes in ways that are hard to understand and can almost seem like a tidal wave. In a passage that is by turns hilarious, disgusting, and soberingly accurate, Toru captures this phenomenon by telling the story of the monkeys of the shitty island.

‘Somewhere, far, far away, there’s a shitty island. An island without a name. An island not worth giving a name. A shitty island with a shitty shape. On this shitty island grow palm trees that also have shitty shapes. And the palm trees produce coconuts that give off a shitty smell. Shitty monkeys live in the trees, and they love to eat these shitty-smelling coconuts, after which they shit the world’s foulest shit. The shit falls on the ground and builds up shitty mounds, making the shitty palm trees that grow on them even shittier. It’s an endless cycle […] What I’m trying to say is this: A certain kind of shittiness, a certain kind of stagnation, a certain kind of darkness, goes on propagating itself with its own power in its own self-contained cycle. And once it passes a certain point, no one can stop it—even if the person himself wants to stop it. (202)

If one can’t tell from the humor of that ingenious passage, Murakami is incredibly apt at making heady moral and philosophical ideas accessible. But he is especially able to do this because of the ordinariness of his main character. Not unlike Bilbo in The Hobbit, Toru Okada is the best possible protagonist for this kind of narrative. He is so utterly normal, so utterly grounded, it’s hard for a reader not to appreciate his stability, even as bizarre, otherworldly things begin to happen. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is a Haruki Murakami novel, after all, and that means you’re in for strange, psychic dreams and dark netherworlds that wouldn’t feel out of place on the X-Files or Twin Peaks (as I noted in my review of Murakami’s Wind/Pinball).

Just in the first chapter alone, a strange woman keeps calling Toru on the phone, insisting that he knows her very well, even though he doesn’t recognize her voice or manner at all… before she takes the conversation in a in a racier direction (“Oh, great. Telephone sex,” Toru thinks to himself before hanging up on her). And then the teenaged girl Toru meets while searching for the his lost cat seems to be rather morbidly obsessed with death. Everyone he encounters is a little strange, a little off, and Toru’s equanimity in encountering them all keeps drawing the reader in.

The balance Toru brings only continues as the aforementioned psychics and strange dreams start to arrive in the novel’s narrative. “What does it all mean?” any reader is bound to ask, but Toru’s even-keeled nature and the connections that are revealed between smaller strange events lead a reader to trust that all the bigger ideas and mysteries Murakami is juggling will come together somehow. And they do—thanks much in part to why this oftentimes somber novel is able to comfort me. Even as Toru uncovers a human darkness that grew out of some of the darkest events of World War II—itself one of the darkest times in human history—he finds a group of like-minded souls, individuals that have learned (or come to learn) how to feel for their fellow humans and to help them.

Still, it all seems so fragile, so impossible. Toru Okada is out of work and his cat has disappeared, shortly before his wife disappears as well. And his primary antagonist is his wife’s elder brother, a rising media star and politician that has all the power and all the cards. It begins to feel like there’s no way that Toru can win and unravel the mystery of those missing in his life, no matter what friends he finds on the way.

But if a small group of humans can continue on, healing the world around them—no matter how high the cost—maybe it’s okay to feel some hope as my own life has been hit by a real-life media (kind of) star and politician that is wreaking his own brand of havoc on this world that I love so much. Like Toru, I choose to descend into the darkness again, for those who seem to be lost to it… unless I can help them find their way out.