The novel begins with simple delight.

The novel begins with simple delight.

The place I like best in this world is the kitchen. No matter where it is, no matter what kind, if it’s a kitchen, if it’s a place where they make food, it’s fine with me. Ideally it should be well broken in. Lots of tea towels, dry and immaculate. White tile catching the light (ting! ting!).

To break down how much this opening does in establishing its modus operandi as well as its narrator and main character, a young woman named Mikage, would take more than the fifty-seven words of that opening paragraph. In the process, I would probably remove far too much of the pleasure it creates, so I’ll just say that if a narrator or narration uses a parenthetical like the above paragraph does to describe something as potentially bland as white kitchen tile, you’ve got me: I am 100% over the moon and in your corner.

So as the short novel continues and we learn Mikage is an orphan raised by her grandmother—and that her “grandmother died the other day,” we realize we have been opened up to feel her grief as rawly as Mikage does. The only spot she’s able to sleep in the apartment she shared with her grandmother is the kitchen: “wrapped in a blanket, like Linus.” The joy of that opening paragraph has been shifted and shot through with grief.

This situation can’t (but could!) continue, so it’s with relief that we see Mikage begin to befriend Tanabe, a young man who worked in the flower shop Mikage’s grandmother frequented—and who liked Mikage’s grandmother enough that he helped with her funeral. He lives with his mother, and he arrives at Mikage’s apartment one day to suggest she come live with them for a bit. Just while she tries to figure things out. Mikage is a bit disconcerted—as most would be—but finds herself liking the idea more and more. Unsurprisingly, on her first visit to Tanabe and his mother’s apartment, she explores the kitchen first: it has a lived-in disorder balanced by the quality of its plates and various implements. “It was a good kitchen. I fell in love with it at first sight.”

Kitchen’s strength is this seeming simplicity. I will admit there are times where either the translation or Yoshimoto’s writing is too simple for me, perhaps missing some of the poetry I prefer or the verve of that opening paragraph, but those moments are few and far in-between. There are far more moments like this for devastating truthfulness:

In the uncertain ebb and flow of time and emotions, much of one’s life history is etched in the senses. And things of no particular importance, or irreplaceable things, can suddenly resurface in a café one winter night. (p. 75)

So many of my favorite moments are ones such as these—reading, playing games, sitting on the porch and staring up at the night sky—letting those memories of important and unimportant things suddenly resurface in my mind’s eye. It’s why for Mikage—and the reader—that grief is not something you just get over or get through, it’s something that remains, becoming a companion that may hold its peace for any number of days, only to return unexpectedly with something as simple as a glancing outside a window of a café.

Most English copies of Kitchen come with a companion piece within its covers, a long story titled “Moonlight Shadow.” Knowing it was a companion piece, I was expecting to find the same characters as Kitchen, perhaps further along their respective paths, but instead it’s a story of two other young people also struggling with the loss of someone close to them: this time, a significant other.

It’s striking in the way grief plays out in similar ways, just with varied surface details. Where Kitchen’s Mikage obsessed over kitchens and cooking, the narrator of “Moonlight Shadow,” Satsuki, has taken up running to cope with the loss of her boyfriend in a car crash. She runs every morning, even when she’s not feeling particularly well, and has started to lose far too much weight. Hiragi, the brother of her deceased boyfriend, lost his girlfriend in the same automobile accident, and he’s gone to the extreme of wearing her uniform to school.

What “Moonlight Shadow” adds to the struggle of learning to live with grief is knowing that you will continue on past the death you cannot forget. That the one you once did everything with will no longer participate in your life as they once did—that you somehow survived and they did not. The story ends with Satsuki calling out to her boyfriend, hoping he will hear her:

Hitoshi:

I’ll never be able to be here again. As the minutes slide by, I move on. The flow of time is something I cannot stop. I haven’t a choice. I go.

One caravan has stopped, another starts up. There are people I have yet to meet, others I’ll never see again. People who are gone before you know it, people who are just passing through. Even as we exchange hellos, they seem to grow transparent. I must keep living with the flowing river before my eyes.

The simple things are how we live and love, as well as how we learn to live with grief, and the simple things are how we are able to continue, even as we cannot forget those we have lost.

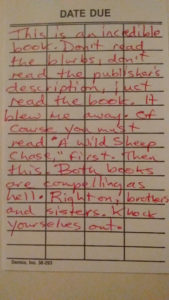

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world.

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world.