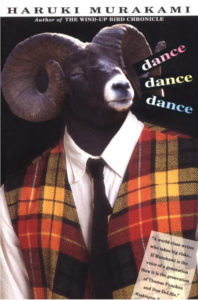

Mood. An important factor in any book, but Haruki Murakami is a master of it. “He’s kind of weird?” people like to say, “but he’s cool, too, I couldn’t get this story of his out of my mind.” If you want to get technical in literary terms, he’s a surrealist, which is the fancier, upmarket way of saying he uses fantastic elements in his work (or a kind of magical realism): his books start out feeling like normal, everyday life, but before you know it, there are crazy conspiracies and alternate realities being fitted into the plot quite neatly and naturally.

Mood. An important factor in any book, but Haruki Murakami is a master of it. “He’s kind of weird?” people like to say, “but he’s cool, too, I couldn’t get this story of his out of my mind.” If you want to get technical in literary terms, he’s a surrealist, which is the fancier, upmarket way of saying he uses fantastic elements in his work (or a kind of magical realism): his books start out feeling like normal, everyday life, but before you know it, there are crazy conspiracies and alternate realities being fitted into the plot quite neatly and naturally.

If you’re a fan of the mesmerizing effect such TV shows as The X-Files, Fringe, or Twin Peaks have (though I have to go from hearsay on the latter), chances are you’ll like the mood Murakami projects in his writing. And there is always something more to Murakami than surreal/genre elements: a truly accessible author, the human condition is always at the heart of of his stories.

There are recurring themes and motifs in all his books (with a quick internet search, you’ll hear quips about lost cats, mysterious women, and a fascination with wells), but each one of his works has a unique focus. They generally have intricate plots and are quite long as well, with one of his more recent novels, IQ84, clocking in at about 900 pages.

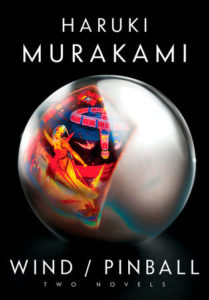

His first two novels, Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball, 1973, were recently re-translated and re-published after being out of print for 30 years (in a fun double book set, with one novel printed on the first half, and the other printed “upside down” on the other half). And if you’re curious about Murakami, you should definitely give these a look.

These two novellas stand out from the rest of Murakami’s body of work in how short and poetic they are, which makes them an excellent starting point for anyone wanting to see if they’ll like his writing. With only 100-130 pages each, you can focus on how Murakami crafts his characters, language, and mood. Both novellas also have a similar structure, as they are made up of short, chronological vignettes that focus on an unnamed narrator in his college years (or a little after, in Pinball), and his friend, nicknamed The Rat.

Hear the Wind Sing

Hear the Wind Sing

For those who have ever felt a little lost or unsure if people get them, for those who have ever felt like they were losing connection with those they were once close to, Murakami gives you Hear the Wind Sing. Set during a summer interlude where the narrator is back home from college (but soon to leave again), the narrator and The Rat are feeling equally unmoored. People come into their lives, then leave. The mood is longing, transitory, even when the two are just shooting the breeze in the local bar. The narrator finds himself wondering about past relationships, particularly with one woman who committed suicide a year or so after they broke up. He starts seeing a girl that seems equally troubled, equally precarious.

Wind is the recurring motif, as the title suggests. It makes characters feel more connected to each other and the world than they ever have before; it makes them lonelier than they could possibly believe. It’s a characterization I can appreciate, as I’ve found there are few things like wind to suggest a person’s current mood and emotion. On a good day with the sun shining, there is little better than to hear the wind soughing through the needles of a pine tree—the world and you are in communion, connected. But on a bad day the same wind might blow hollow, reflecting the emptiness inside you in an echo chamber of depression.

For all its quiet loveliness and truth, there are some odd vignettes and inclusions in Hear the Wind Sing. It’s not as well-crafted as Murakami’s later work, but it’s still the writing of a masterful author. In his introduction, Murakami notes that he wrote the novel in the early hours before dawn, after returning from work at a jazz bar he and his wife owned. The bar was struggling and just finding its feet, while he was in the last years of his 20s and trying to find his way.

This book is the feeling you have when you awake (or can’t fall asleep) in the small hours of the night, mind humming with ideas, filled with a nameless longing.

Pinball, 1973

Pinball, 1973

For those who have ever wondered where they were headed or if what they were doing matters, for those who have ever wondered why things have to change, Murakami gives you Pinball, 1973. Told in short, chronological vignettes similar to Hear the Wind Sing, we once again follow the small biographical ins and outs of the nameless narrator and The Rat. It’s set a couple years after the previous book, and the nameless narrator lives in Tokyo, while The Rat is still bumming around the narrator’s hometown, drinking beer at the local bar and living off of his rich father’s money.

The unmoored feeling of the previous book continues, but with a feeling of loss and damage, accentuated by the fact that the narrator and The Rat never meet. We get the feeling they’re still friends, but they’re apart. And the season is fall: change is in the air.

In one haunting segment, The Rat stares at an old, small lighthouse at the end of a pier. He’s longing for something, but something also feels wrong: as another section notes, “we could sense something nasty lurking just out of sight.” When I read, no, when I saw The Rat watching the old lighthouse, I was like, “This is me, at the end of grad school in 2004.” My maternal grandfather had passed away earlier that spring; I wasn’t quite sure what to do with my life or what it all meant. I spent hours walking by Lake Superior, staring at the waves and Duluth’s lighthouses. I didn’t yet know that my father had cancer.

It’s a feeling I’ve had at other times in my life as well. The truth told in the mood of this book still astounds me.

There are still weaknesses, I suppose. Being Murakami’s second book or novella, there are some bits that seem a little off to me. But even then you can see his progression as an author: themes and images are coalescing for him, which will reappear, fully formed and developed in his later work. Surreal elements which were not about in his first novella begin to make their appearance in the unnamed narrator’s hunt for a pinball table he was obsessed with playing during college. I think every reader will have a different take on the meaning of the strange warehouse the narrator eventually finds the pinball machine in, but there are undoubted echoes of his relationship with a woman that is now dead (possibly the same woman mentioned in Hear the Wind Sing). There is always some doubt or guessing to Murakami’s work, as with all great literature, but more is probably unclear here than there should have been.

Another Murakami trope, mysterious women, appear in the guise of two twins that live with the narrator for awhile. They seem real and they do not seem real at the same time. Their entrance is unclear: did the narrator meet them somewhere one night and just wake up next to them in the morning, unable to remember how he met them? Or did they literally appear out of nowhere? You could read the text either way. They do have substance, other characters in the book see them, but they are undoubtedly not like the other women in the book, who are struggling just as the narrator and The Rat are struggling.

Whoever or whatever the twins might be, they seem to be there to help the narrator deal with an unnamed trauma (probably the woman who has died, but again, the novel is a bit unclear on the details), and then they go away when he is able to deal with it, or at least bring it to terms. I’m still not sure if the twins are a weird thing for Murakami to include or if they are a perfect fit for the novel’s feeling of transience, but I do know I feel more ambivalent about them than the other mysterious women that tend to pop up in his books.

Regardless of its shortcomings, however, Pinball is a beautiful read. What feeling is it? Unlike with Hear the Wind Sing, I’ll let Murakami take us out on this one, as there is no way for me to capture it perfectly.

“{The Rat} was as powerless and lonely as a winter fly stripped of its wings, or a river confronting the sea. An ill wind had arisen somewhere, and it was blowing the warm, familiar air that had embraced him to the other side of the planet.

One season had opened the door and left, while another had entered through a second door. You might run to the open door and call out, Wait, there’s something I forgot to tell you! But no one is there. When you close the door, you turn around to see the new season sitting in a chair, lighting up a cigarette. If you forgot to tell him something, he says, then why not tell me? I might pass the message along if I get the chance. No, that’s all right, you say. It’s no big deal. The sound of wind fills the room. No big deal. Just another season dead and gone.”

It’s actually become a critical trope in and of itself to say there are no new stories (in other words, every tale is simply made up of well-known narrative techniques). I’ve never been a fan of such over-generalizing, but it is worth noting how a newly created movie or book makes use of all the stories that have come before it. Some can approach things in such a fresh way that they seem completely unlike anything before, much like The Lord of the Rings and Star Wars: A New Hope did when they first arrived. And others can seem hopelessly imitative, like Eragon: it’s still an impressive story for a teenager to write, but the patchwork quilt of its influences is mighty noticeable.

It’s actually become a critical trope in and of itself to say there are no new stories (in other words, every tale is simply made up of well-known narrative techniques). I’ve never been a fan of such over-generalizing, but it is worth noting how a newly created movie or book makes use of all the stories that have come before it. Some can approach things in such a fresh way that they seem completely unlike anything before, much like The Lord of the Rings and Star Wars: A New Hope did when they first arrived. And others can seem hopelessly imitative, like Eragon: it’s still an impressive story for a teenager to write, but the patchwork quilt of its influences is mighty noticeable. What makes The Dragon Prince such a standout for everyone to watch (it is NOT just a children’s animated series, no matter how much the Daytime Emmy’s want it to be) is how it takes these familiar elements in powerful new directions. One in particular that stands out from many previous fantasy films and shows is its inclusivity: Humans and elves are drawn in ways that will remind viewers from this reality of various Earth cultures and regions, but no one in the world of The Dragon Prince notices or makes a comment about another person’s accent or skin tone. That’s just how they look.

What makes The Dragon Prince such a standout for everyone to watch (it is NOT just a children’s animated series, no matter how much the Daytime Emmy’s want it to be) is how it takes these familiar elements in powerful new directions. One in particular that stands out from many previous fantasy films and shows is its inclusivity: Humans and elves are drawn in ways that will remind viewers from this reality of various Earth cultures and regions, but no one in the world of The Dragon Prince notices or makes a comment about another person’s accent or skin tone. That’s just how they look. Probably the most powerful statement the show creates from its familiar elements is about choice: why are you doing what you are doing, and to what end? Not thinking about the true end of their choices is a consistent problem for its characters, and sets up the crux of the storyline for the show’s three seasons. At its beginning, a group of elvish assassins have been sent to kill a human king and his heir, the human king having himself killed the King of the Dragons previously (out of revenge for the death of someone else). As the viewer learns more, they begin to see that this is just the most recent in a long history of humans and magical creatures pursuing vengeance or power (the one sometimes mistaken for or blended with the other).

Probably the most powerful statement the show creates from its familiar elements is about choice: why are you doing what you are doing, and to what end? Not thinking about the true end of their choices is a consistent problem for its characters, and sets up the crux of the storyline for the show’s three seasons. At its beginning, a group of elvish assassins have been sent to kill a human king and his heir, the human king having himself killed the King of the Dragons previously (out of revenge for the death of someone else). As the viewer learns more, they begin to see that this is just the most recent in a long history of humans and magical creatures pursuing vengeance or power (the one sometimes mistaken for or blended with the other).

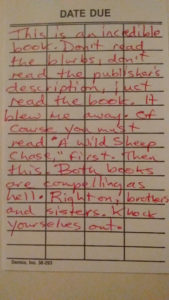

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world.

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world. Mood. An important factor in any book, but Haruki Murakami is a master of it. “He’s kind of weird?” people like to say, “but he’s cool, too, I couldn’t get this story of his out of my mind.” If you want to get technical in literary terms, he’s a surrealist, which is the fancier, upmarket way of saying he uses fantastic elements in his work (or a kind of magical realism): his books start out feeling like normal, everyday life, but before you know it, there are crazy conspiracies and alternate realities being fitted into the plot quite neatly and naturally.

Mood. An important factor in any book, but Haruki Murakami is a master of it. “He’s kind of weird?” people like to say, “but he’s cool, too, I couldn’t get this story of his out of my mind.” If you want to get technical in literary terms, he’s a surrealist, which is the fancier, upmarket way of saying he uses fantastic elements in his work (or a kind of magical realism): his books start out feeling like normal, everyday life, but before you know it, there are crazy conspiracies and alternate realities being fitted into the plot quite neatly and naturally. Hear the Wind Sing

Hear the Wind Sing Pinball, 1973

Pinball, 1973 Friday night, Jessica and I had a decision to make: were we going to see Lego Batman or Moonlight? We ended up choosing the latter, partially under the logic that plenty of people were going to see Lego Batman, and we might as well reward the theater for picking the less popular but more serious movie, which had just won an Oscar for Best Picture.

Friday night, Jessica and I had a decision to make: were we going to see Lego Batman or Moonlight? We ended up choosing the latter, partially under the logic that plenty of people were going to see Lego Batman, and we might as well reward the theater for picking the less popular but more serious movie, which had just won an Oscar for Best Picture.