Rom-coms have a clear formula: the potential love interests meet early on in the story, the potential love interests face obstacles in getting together, the love interests then finally get together (potentially facing more obstacles before they are for real together together). Simple.

Rom-coms have a clear formula: the potential love interests meet early on in the story, the potential love interests face obstacles in getting together, the love interests then finally get together (potentially facing more obstacles before they are for real together together). Simple.

Why the rehash of a well-known genre, you ask? Because reviewers and whoever does the posters and promos at Netflix seem to think the limited series From Scratch is a rom-com. Some critics compared it to typical (if “elevated”) fare from Hallmark and Lifetime during the holiday season, and Netflix itself recommends viewers of the limited series to check out Love & Gelato (very much a rom-com) and Emily in Paris, which… I guess they’re related, if you want to watch something where an American goes to live in Europe for awhile?

It’s a frustrating diminishment of a moving drama based on Tembi Locke’s memoir of the same name. Created and partially written by Locke and her sister, Attica, the series follows Zoë Saldaña’s Amy, who meets future husband, Lino (played by Eugenio Mastrandrea) while studying abroad in Florence. The closest the series gets to the rom-com formula is its first episode, but even here one can see the deeper dramatic themes the series exemplifies: beginnings (and endings), beginning after an ending, and the emotions that so often characterize beginnings and endings—grief, love, hope, and regret. The stakes are also much more real than in a rom-com, with their often disposable significant others who are clearly not meant for one of the story’s potential love interests. This difference is made very clear in the first episode when Lino confronts Amy about doing something that has clearly hurt him to the core. Amy, who has mostly been treating her relationship with Lino (and others) like a short-term, just for fun, compartmentalized study-abroad experience, is forced to realize what she’s doing matters to him, and her.

The first episode also sets up another major factor the series will deal with, which are the realities romance must deal with in the real world: towards the end of her time in Florence, Amy is visited by her father (played by the inimitably voiced Keith David) and step-mother. Amy’s father is keen to get her back in law school and away from this art business she’s been studying in Florence. Her step-mother, played with a lovely warmth by Judith Scott, is equally keen to keep the peace.

It’s an experience many can relate to from their teens and twenties (or maybe even later), where conflicts flourish between the generations as the grown-up child begins to conform less and less with what their parents thought they were going to be. But what makes the series particularly lovely is how many years it traces (well over a decade): we see Amy’s relationships with her father, step-mother, and mother all develop, shift, and grow as she and Lino eventually marry, then adopt a child of their own some years later. And we get to see this happen with Lino’s family as well. Cultural misunderstandings abound, but are also worked through in ways that are not quick, easy, or melodramatic—the result feels much more real than the vast majority of dramas out there.

This is all assisted by there being no weak characters in the supporting cast of family and friends, as well as how excellent Saldaña and Mastrandrea are as the series’ leads. Even so, the standout in the familial relationships is Amy’s sister, Zora, played by Danielle Deadwyler. As Amy’s older sister, she clearly carried some of the weight for Amy as they both navigated their parents’ divorce, who separated while they were children. Rather than being a one-note supporting role, we see Zora as a fully rounded person. She is sometimes frustrated and annoyed with both Amy and Lino (particularly when they are forced to live with her for an extended period), but when it comes down to it, she is always there for them, no matter what heartbreak may come their way. Seeing such a fierce, loving, and caring person played with such depth is far too rare in storytelling, and Deadwyler’s sheer power and presence in the role makes it clear how important having such a person in your life can be.

It’s rare for stories to take the time to grapple with life so wholly as From Scratch does, and it being a limited series means it won’t be back for more, trying to scrounge up additional drama or character failings like some series have to do when they’re extended. It told the story it wanted to tell, and it actually left me emotionally rocked and in tears more than once—no mean feat, and certainly not something a rom-com is generally able to do (no matter how much I enjoy that genre). From Scratch is a family drama about love, life, and death, and it is not to be missed.

(Important, pre-blog post note, as this was drafted three weeks ago: opinions are opinions and not to be confused with facts)

(Important, pre-blog post note, as this was drafted three weeks ago: opinions are opinions and not to be confused with facts) The problem with that? Opinions are like butts: everybody got one. Once we’re Covid free, singles aren’t going to stop liking their singlehood for the time being (or for some, wishing and longing they were not single). Relationship holders are not going to stop loving (or pretending to love) their relationship. And meddlesome relatives and friends aren’t going to stop suggesting to the single person they know that the right man/woman/person for them might be just around the corner.

The problem with that? Opinions are like butts: everybody got one. Once we’re Covid free, singles aren’t going to stop liking their singlehood for the time being (or for some, wishing and longing they were not single). Relationship holders are not going to stop loving (or pretending to love) their relationship. And meddlesome relatives and friends aren’t going to stop suggesting to the single person they know that the right man/woman/person for them might be just around the corner. If everybody got opinions, are we condemned then to stand in our wrongness and be wrong and get used to it (no matter how amusing it was

If everybody got opinions, are we condemned then to stand in our wrongness and be wrong and get used to it (no matter how amusing it was

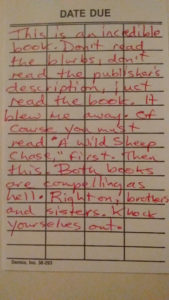

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world.

An additional piece of magic happened for me with my library book, however. A former reader had co-opted the old checkout tag to leave a note for future readers, in a manner that feels almost trademark Murakami. His narrators are always getting odd messages or stories told to them, and this one is no different. The weird energy of that note is wonderfully sublime and needs sharing with the world. In non-BFS fashion, I’m going out on a limb and making a big statement I haven’t mulled over ad nauseum. In my cautious, middle child way, I like to settle into what I’m thinking and saying, but I felt compelled to make this leap after reading

In non-BFS fashion, I’m going out on a limb and making a big statement I haven’t mulled over ad nauseum. In my cautious, middle child way, I like to settle into what I’m thinking and saying, but I felt compelled to make this leap after reading